Summary by Jenn David-Lang

The Distance Learning Playbook, Grades K-12

By Douglas Fisher, Nancy Frey, and John Hattie (Corwin, 2021)

What are the main ideas?

- This book takes the research on what improves student learning, along with lessons from recent crises, and applies that to our current situation with distance learning.

- Just because they are not face-to-face with students, teachers did not forget how to teach and this book provides the types of familiar tasks and ideas they can implement to ensure students learn.

What are the main ideas?

- This book takes the research on what improves student learning, along with lessons from recent crises, and applies that to our current situation with distance learning.

- Just because they are not face-to-face with students, teachers did not forget how to teach and this book provides the types of familiar tasks and ideas they can implement to ensure students learn.

Why I chose this book:

With remote teaching, I’ve seen how hard teachers have been working and how burnt out many of them feel. I know leaders want to do whatever they can to help teachers ensure their students learn and feel supported during this time.

That’s why I was so thankful and inspired that these three outstanding authors put together such a useful resource so quickly! As Douglas Fisher says in the introductory video, we are living in an exciting and stressful and anxiety-producing time in education but we can still impact student learning. Teachers haven’t forgotten how to teach. Plus, there is deep research that can inform what teachers need to do to make distance learning effective.

There are no quick answers and this book is not a collection of tech tools. Instead, the authors urge educators to build on what we already know about effective teaching and learning and apply that to make distance learning both deep and engaging for all students.

Note that there are some fantastic free videos and resources that accompany this book on Corwin’s website: https://bit.ly/corwinbk.

In this summary you will learn…

- Module 1 – Some brief, yet impactful suggestions to help teachers prioritize self-care

- Module 2 – Preparing for the first days of school with expectations, routines, and procedures

- Module 3 – The characteristics of positive teacher-student relationships and how to implement them

- Module 4 – Building teacher credibility at a distance through trust, competence, dynamism, and immediacy

- Module 5 – Five important steps to improve teacher clarity at a distance – align standards, units, aims, and success criteria

- Module 6 – How to engage students in meaningful tasks that allow them to demonstrate learning

- Module 7 – The 4 components of quality instruction at a distance: demonstrating, collaborating, facilitating, & practicing

- Module 8 – Opportunities for using feedback and assessment for student growth even at a distance

- Module 9 – Using what we’ve learned from crisis teaching to make schools better

- PD ideas, including a PPT and HANDOUT for teachers, from THE MAIN IDEA – at the end

Introduction:

The world has been completely changed by the recent pandemic. It is unclear what will happen with schools as they reopen. Some schools will use a hybrid of online and in-person instruction, while others may conduct all instruction at a distance. While many teachers already taught remotely in the early part of 2020, this was not distance learning. Rather, this was crisis instruction.

Now that schools have time to plan for the re-opening of schools, there is an opportunity to take what we learned from this crisis teaching and what we know about effective instruction from research, particularly from the three authors of this book, and be much more effective in meeting student learning needs.

For example, below are some things we learned during the recent pandemic that are reinforced by Visible Learning research. Learning is most effective when:

- We foster student self-regulation.

- The student, not the teacher, is at the center of the instruction.

- Peer learning is utilized.

- There are a variety of pedagogical approaches not just direct learning and then some off-line independent work.

- Feedback is an integral part of the learning cycle.

Research and Distance Learning

Much of the research in this book comes from John Hattie’s Visible Learning research. This research has examined the impact of a number of factors on student learning and to date, it includes over 1,800 meta-analyses with over 300 million students! Factors that have higher effect size (that is, more than .40) are ones that accelerate students’ learning (see the effect sizes of different factors here: visiblelearningmetax.com). It doesn’t mean the rest don’t work, but they need to be implemented cautiously.

For example, distance learning has a small effect size (0.14) which again, doesn’t mean it does NOT work, but it does mean that teachers need to think carefully about how they implement it. It helps to look at the effect sizes of different technology tools. For example, research shows that interactive videos have an effect size of 0.54 while the presence of mobile phones is -.034 (yes, that’s negative, and it’s why the authors explicitly state, “Please turn them off.”)

This is why teachers need to think more about the methods of teaching than the medium. Technology should be seen as the means not the ending point. It is the teacher’s tasks and decisions that are key to student learning:

- Do we give students opportunities to interact with each other (and not just get talked to)?

- Do we check for student understanding as we teach to determine the impact of our instruction (particularly in distance learning)?

- Do we balance content knowledge with deep learning (unfortunately, in distance learning we tend toward the former)?

Equity

Those students whose learning was comprised before the pandemic continued to experience this risk during distance learning. For a list of suggestions to help educators intensify their efforts to meet the needs of these students, take a look at this continually updated list of resources from the San Diego County Office of Education: https://bit.ly/2A55c1j.

Then there are additional students who had not been considered at risk in the past, but whose needs spiked during the pandemic. These are students who struggle with self-regulation, experience high levels of stress, have homes that are not safe, and have parents who couldn’t or wouldn’t support their engagement in schoolwork at home. Throughout the book there will be examples of these types of needs and how educators can address them.

Module 1 – Take Care of Yourself

It might be surprising that the authors begin a book about distance learning with a chapter on self-care. However, most educators didn’t sign up to teach through a screen and if we don’t learn to handle the stresses that come with this newer form of instruction, we will burn out and we won’t be able to deliver quality distance learning for our students.

Further, we won’t be able to serve as role models of resilience at a time when many of our students are experiencing the adverse effects of trauma. For this reason, we need to pay attention to the social-emotional needs of the adults as we move forward. Below are some suggestions that have emerged from what has worked in other stressful times that can apply to educators working from home during the pandemic.

Workspace

The first suggestion for working successfully from home is to create a dedicated work space for yourself. This doesn’t mean you need a “home office” – a corner of the kitchen with nice light or a quiet unfinished basement will do the trick. Gather the supplies you need and other typical classroom items so it will look more like “school.”

You may also need some ground rules for others who share your space – perhaps a sign to let people know you’re working or a request to use the noisy washing machine on weekends. This doesn’t mean there won’t be interruptions – a cat who jumps in front of the screen or a child who interrupts. Everyone will understand.

Routines

Many of the routines that help us organize our day were disrupted with stay-at-home orders. It is extremely useful to re-establish some routines to provide structure and help delineate your work and home lives. You might start your day with a 20-minute walk or reading. Perhaps you have a visual cue that your work day will begin, like Mister Rogers, by changing your clothes. It’s a good idea to plan breaks for lunch or a recess during the day as well. End-of-day routines are useful for closing out the work day – perhaps a mental recap of what you’ve accomplished or a 20-minute meditation.

Socialization

One of the things educators miss by not teaching in a physical building is all of the ad-hoc socialization opportunities in the halls or teacher lounge. It will help to be purposeful about connecting with colleagues both on- and off-line. It also helps to connect with others outside of your school. You might consider committing to sign up for one online professional learning opportunity each month. Or have a coffee (virtual or in-person) with one person each day who is outside your home.

Physical health

Finally, in addition to the above three types of support, nothing is more important than remembering to take care of yourself physically. Eating well, exercising, and managing your stress are particularly important in ensuring your well-being during this difficult time. It’s a lot easier to say these things than to do them, so perhaps you might choose a commitment partner and regularly check in about your goals to keep yourself healthy.

Compassion fatigue

Sometimes it’s hard to keep all of the above suggestions together and educators experience what is called “compassion fatigue – a state experienced by those helping people in distress; it is an extreme state of tension and preoccupation with the suffering of those being helped to the degree that it can create a secondary traumatic stress for the helper.” (p.20) If you are experiencing isolation, emotional outbursts, apathy, persistent physical ailments, substance abuse, or other personal, emotional, or physical signs, reach out for help. Your students need you and compassion fatigue can be addressed.

Module 2 – The First Days of School

Whether you start the school year face-to-face or with distance learning, the authors emphasize the importance of starting off on the right foot. Research has shown that this can make the difference between an effective, efficient, well-run class and one that is not. This module helps teachers through what they need to do to create a classroom management plan. This plan includes the procedures, routines, and expectations for your class. The key is to be proactive so you are not deciding in the moment how to respond.

One helpful way to begin is to create a statement of your teaching and learning philosophy. When you are clear about your beliefs, your expectations for the classroom environment and how students will interact with each other will flow more readily.

One sixth grade teacher wrote the following brief teaching philosophy and posted it on her digital classroom wall:

“I value an environment that allows people to take risks and make mistakes.

We are all learning new things and we are here to help each other.”

The rest of this chapter will help you map out your classroom management plan. Once you’ve done so, you can translate it into student-friendly language and post it, along with your philosophy, on your learning management system (LMS) to share with students and families.

Establish Norms and Expectations and Link Them to Class Agreements

Norms are what describe how people interact with each other. If you don’t set these up, they will emerge from the group. For example, when a group of friends get into the habit of regularly insulting each other. Unfortunately, with the rapid pivot to distance learning, norms were forgotten in many classes.

It is worth taking the time to outline how students should interact in the virtual classroom. Take the norms you would use in a regular classroom about being respectful and translate those to the virtual space – how do you want students to comment on each other’s posts? How do you want students to show they are paying attention to peers in online sessions? Below is what research shows makes norms more effective:

- Stick to a few norms (3-5 is best).

- Outline the expected behavior specifically.

- Co-construct them with your students.

- Post the norms on a chart behind your head in a virtual classroom.

- State them positively rather than starting with “No.”

- Teach and rehearse the expectations.

Note that some expectations will be specific to synchronous distance learning. For example, a number of teachers experienced resistance to the expectation of turning on the camera. There are a number of reasons students resisted this. 20 percent of students are Muslim and female family members don’t wear the hijab at home. Other students didn’t want to share images of their homes. A solution is to have students either turn on their video or use a school picture and try to turn on videos once in breakout rooms. Some schools continued with the expectation that students wear their school uniforms in synchronous learning situations.

Develop and Teach Organizational and Procedural Routines

To help students become organized, another part of your virtual classroom management plan should focus on procedures and structures needed for the classroom. Because students may be juggling different classes and families may have more than one school-aged student at home, it helps to provide daily, weekly, and monthly schedules.

Further, actively teach students the signals you will use to get everyone’s attention and transition to new activities. Some online platforms have an elapsed timer display to help. These schedules and signals not only help to create a predictable environment, but they are incredibly useful for students new to English, students who struggle with transitions, and students with behavioral difficulties. Finally, be sure students know how to get the materials they need (label digital folders clearly) and how to submit assignments.

Your First Distance Classes

Take the same goals you would have for a face-to-face classroom and apply them to the distance-learning environment. For example, be sure to greet students by name as they enter. Try to personalize the space as much as possible. You might create a word cloud of students’ names to use for your virtual background. Even online, be sure to learn and use students’ names and pronounce them correctly. If you use songs and chants with younger students in person, continue to do so online.

If you have adolescents interview and introduce each other the first few days, do this online as well. Finally, it is particularly important to learn about students’ interests with distance learning. Have students fill out interest surveys or interview each other in order to build positive classroom relationships. Keep a chart of the results so you can refer to them. Imagine the power of sharing an article with a student and saying, “I read this and I thought of you.” The first few days of virtual school is a crucial time to forge relationships and set up the class for success.

Module 3 – Teacher-Student Relationships From a Distance

Without a doubt, knowing how to make a connection with your students is one of the most important traits of an effective teacher. Research shows that teacher-student relationships positively impact learning with an effect size of 0.48. Clearly, getting to know your students’ individual aspirations and stories is key to good teaching, and perhaps even more important when teaching from a distance.

Characteristics of Effective Teacher-Student Relationships

Positive teacher-student relationships are important in general, and probably more so in remote learning. The authors outline five characteristics of these positive relationships (empathy, positive regard, genuineness, student-centered approach, and encouragement of critical thinking), three of which are described below (see p.51 for descriptions of the others):

1. Teacher empathy (understanding)

How will you build connections with students?

Examples of implementation

- Start classes with positive affirmations – jokes, videos, quotes.

- Hold virtual office hours for support.

- Hold brief check-in conferences with families and individual students.

2. Unconditional positive regard (warmth)

How will students know you care about them?

Examples of implementation

- Weave students’ interests and pursuits into lessons.

- Provide polls for students at the end of classes.

- Use voice feedback tools on student work so they hear your voice.

3. Nondirectivity (student-initiated and student-centered activities)

How will students know you value their abilities?

- Hold conferences with students to help them identify strengths and goals.

- Promote thinking with student-centered activities (in distance learning sessions allow students to write about, illustrate, or discuss thinking with peers).

- Used shared decision-making with students around the curriculum.

Teacher Impact on Peer-to-Peer Relationships

It’s interesting to note that the teacher’s relationships with students also impacts students’ relationships with each other. For example, if a student asks an off-topic question, the way the teacher responds signals to the rest of the class how to treat that student. If the teacher responds negatively or has a dislike for the student (and peers often pick up on such a feeling) then the teacher is modeling how students should interact with that student.

This is even more the case with remote learning. The video provides a close-up of your reactions and nonverbal signals and it is clear when you stop listening to a student. Further, your feelings are clear to all when you mute a student’s microphone for asking off-topic questions. The result? Either students will join you in your dislike for that student or they may take a dislike to you; both of which undermine learning.

Reaching the Hard to Teach

There will always be some students we feel less in synch with – they rub us the wrong way or keep us at a distance. And it is understandable that we would gravitate toward the types of students that make us feel more successful in our jobs. However, research has shown that when there are students we are not as close to, in particular low-achieving students, this often impacts how we interact with them. We are less likely to praise them, give them feedback, call on them, and more likely to criticize them.

What about trying to turn this pattern around? Consider going out of your way to give those “hard to reach” students increased positive attention. Perhaps those students would start to bloom and your opinions of them might change. Try keeping track!

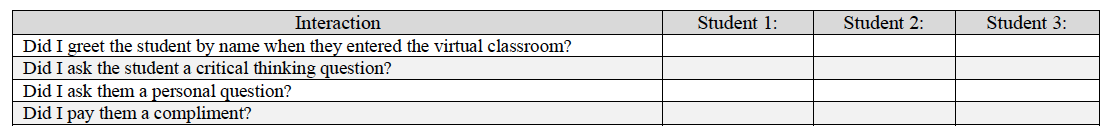

Increase Your Touchpoints with all Students

Teaching virtually means that we have far fewer touchpoints with students. We don’t see them in class and we no longer have casual interactions in the halls or cafeteria. Not only do we have less contact, but when we do see students in live sessions, we mistakenly use that time for direct instruction which means even less interaction. Below are some suggestions to maximize interactions:

- Use a system for calling on students and note who hasn’t participated. This might mean randomly selecting students from a stack of cards with their names and then keeping a tally of who has spoken.

- Include small- as well as whole-group sessions, and keep lectures short.

- If you use discussion boards, actively participate in them yourself.

- Keep up the touchpoints in between live sessions. Use Remind messages, send emails, create videos for asynchronous assignments rather than written instructions, and use voice recordings for feedback on assignments to make it more personal.

Module 4 – Teacher Credibility at a Distance

One of the most important questions teachers can ask is, Do your students believe they can learn from you? According to research, the effect size for teacher credibility is incredibly high: 1.09!!! Without teacher credibility it’s hard to imagine students learning anything. While you may think teacher credibility is similar to the last module’s topic – teacher-student relationships – it actually encompasses more than that. In fact, teacher credibility includes the following four areas: trust, competence, dynamism, and immediacy.

Matt Anders’s credibility comes through strong and clear in his virtual algebra class. Before he gives a test, he allows students to take a practice exam as many times as they need for additional learning. He also provides the students with a video that introduces the practice test, “Greetings Algebrains! You’ve worked hard and I hope you’ll trust me and yourselves to complete the practice versions on your own. I’ll be online for three hours and we can work together any time you need help. I’m not here to trick you — I know you know this material.” You can see the four elements of teacher credibility (trust, competence, dynamism, and immediacy) from the way he shows up for and encourages the students to be successful. Below are other actions to boost teacher credibility:

Trust

Students want teachers who are reliable and true to their word. Below are a few key actions teachers can take to build this trust:

- Keep the promises you make (or explain why if you cannot).

- Tell students the truth about their performance (they know when their work is not up to par).

- Don’t focus on trying to catch students doing something wrong (but be honest about the impact of their behavior).

- Examine negative feelings you have about specific students (they can perceive that even in a virtual classroom).

To develop trust in distance learning it is particularly important to show up looking like a teacher, on time, and with a positive spirit. To show you are reliable, if you ask students to bring something to or do something for class, be sure to use those items. Students know when teachers aren’t being genuine – like when they give everyone a “10” on their online discussion board comments or write “good work” on submitted assignments. The lack of honest feedback signals that you didn’t care or didn’t spend the time.

Competence

In addition to having trust in their teachers, students also want to know that their teachers are competent — that they know what they’re teaching and how to teach it. Below are a few actions that communicate a teacher’s competence:

- Be sure to know your content well but be honest when a question arises that you’re unsure about.

- Organize lessons in a clear and cohesive way.

- Make sure your nonverbal behaviors communicate competence – watch your hands and facial expressions.

Exuding competence may seem challenging if distance learning makes you feel like a first-year teacher again! Rather than thinking of this as a colossal pain, try to think of it as a learning opportunity. Don’t try to master a ton of tech tools, instead focus on a few that serve the functions you need. Be honest when a tool is new, but share your excitement for learning as well. One teacher was trying her first live video session and started it by saying, “So, this is my first time doing this. I’m a little nervous, but also excited. At the end, I want to ask for feedback. I want to be sure that you’re learning and I’m willing to make adjustments.” The students were kind and offered three invaluable pieces of feedback to help her improve her live video sessions.

One thing that signals to students a lack of competence is when teachers continually change instructional strategies. Instead, build competency by creating predictable learning routines. For example, one middle school teacher, Arnold Anaya, laid out the following:

Mondays – Students watch him on video. He records lots of short videos with information and embedded quizzes for practice.

Tuesdays – He models his thinking in several live readings a day (so students can choose) with questions in the chat.

Wednesdays – Students receive an assignment to find current information that relates to the topic they’re studying that week.

Thursdays – Students have collaborative tasks and virtual labs. He also offers tutorials. These are optional for all and required for those students who showed they needed help in the pre- assessment or who have disabilities. The special educator joins him.

Fridays – Quizzes and writing tasks. Students re-take quizzes as many times as they’d like if they explain their incorrect answers.

Dynamism

This aspect of teacher credibility is about communicating your passion for your content and the classroom. To improve dynamism:

- Rekindle your passion by remembering why you wanted to teach in the first place and the content that most excites you.

- Bring relevance to your lesson by making outside connections, giving students opportunities to learn about themselves, connecting to universal human experiences, presenting ethical concerns, and getting students engaged in the community.

- Seek feedback from trusted colleagues about your lesson delivery by having them sit in on a virtual lesson.

Immediacy

This part of teacher credibility has to do with how accessible and relatable you are. It is harder to be accessible in a virtual setting in the same way as in the classroom – through moving around the room and interacting with students. To do this in a virtual space, teachers might try to pop in to breakout rooms, use student names so they hear their names at least once a day, look at students and smile, use vocal variety, and invite students to provide feedback – all of which will increase immediacy.

Module 5 – Teacher Clarity at a Distance

In distance learning, students should be able to answer these questions each day: What am I learning? Why am I learning it? and How will I know if I am successful in my learning? A student’s ability to answer these questions is a matter of teacher clarity. Teachers must be able to clearly communicate learning goals with students and develop concrete lessons that support student mastery of these goals. Teacher clarity is especially important during distance learning because students don’t have the reminders and cues that keep them focused in physical classrooms. This chapter presents five important steps to improve teacher clarity. These actions ensure that students understand what they are learning so they can take an active role in their education and monitor their own success.

Step 1: Start with the Standards: Build deep knowledge of required concepts and skills

Most teachers develop their learning goals or “intentions” from grade-level content standards. Therefore, to improve clarity, teachers should be crystal clear about what the standards mean. One good way to analyze the standards is to examine the nouns, which provide clarity about the concepts and the verbs, which provide clarity about the skills students must master. For example, look at the nouns and verbs in the following standard: Explain how the ideology of the French Revolution led France to develop a democratic despotism. Here, the concepts would include ideology, the French Revolution, and democratic despotism while the skill is to be able to explain. Teachers must define mastery of each concept and skill in order to build clear learning goals and lessons.

Step 2: Develop Concrete Learning Units

Once teachers are satisfied with their knowledge of the standards, they can plan their learning units around these concepts and skills. At this stage, teachers map out the “flow” (i.e. learning progressions) of their instruction. This is where a teacher’s grasp of the standards becomes essential: An informed teacher understands which standards-based concepts and skills logically build on others – and she can use that knowledge to design units that support student development.

Learning units should also include details regarding any new terms or concepts students must know to be successful, and teachers should be prepared to teach new vocabulary directly so students can easily navigate required readings and tasks. Finally, the authors recommend that teachers be mindful of time when planning units: They recommend limiting distance learning units to no more than two to four weeks since longer units tend to wear on students and lead to disengagement. See the “Planning Template” on the Corwin resource page for more guidance on unit planning.

Step 3: Design and Share Learning Intentions

After teachers complete their learning units, they can focus on their daily learning intentions. In every lesson, learning intentions should be clearly stated. For example, in Mr. Gavin’s physics class, his first unit focuses on electrical current, potential difference, and energy flow. His initial learning targets include: “I am learning that an electric charge can be positive or negative” and “I am learning about the law of conservation of electric charge.” Writing the intentions first – before designing daily tasks – ensures a clear connection between the expectations expressed in the standards and the actions taken in the classroom.

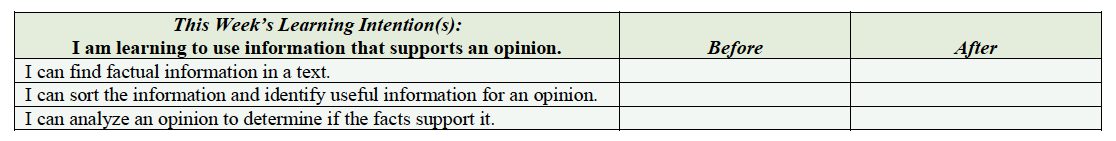

Teachers can share their learning intentions with students in a variety of ways. In distance learning, they can post them on the opening page in the LMS, in a chat box during a live session, or at the beginning of a pre-recorded video. Teachers can also use a weekly “distance learning log” with students. One sample log includes the week’s learning intention and the success criteria with space for the student and the teacher to rate learning before and after each lesson:

Step 4: Communicate Success Criteria

To improve clarity, teachers should also provide students with success criteria to ensure they understand what mastery looks like. Specifically, success criteria clarify mastery of a required concept or skill. There are many ways to communicate these criteria with students. In the learning log example above, “I can” statements are especially helpful in distance learning because they allow students to monitor their progress toward mastery on a weekly basis. Teachers can also use checklists, rubrics, exemplars, and modeling. Teachers should use a combination of strategies to help students recognize success. For example, a student might not immediately understand a writing checklist that describes the need for a “strong concluding statement,” but a checklist combined with a discussion of exemplars can provide clarity. Tip: The Chapter 5 videos on the Corwin resource website include examples of these strategies.

Step 5: Make Learning Relevant

As a final note, the authors encourage teachers to help students make connections with their learning. When learning feels relevant, student engagement increases. The authors present relevance on a continuum from “least” to “most relevant.” Personal association (i.e. a connection to an object or memory) has the least relevance, while activities that enhance students’ personal identity has the greatest potential to engage students.

Module 6 – Engagement

In the rapid move to distance learning, many schools became too focused on the technology tools themselves. Concerns regarding “installation and operation” took precedence over usefulness or effectiveness. This chapter explores what teachers can do to create truly engaging learning for students. (Hint: It doesn’t require more technology.)

Engagement Matters

All educators know students must be engaged to learn. Student engagement is more than just cataloguing who is logging into their computers or turning in their assignments. It is typically assessed across three dimensions: behavioral, cognitive, and emotional.

Behavioral engagement – a student’s observable academic actions, including class participation and assignment completion. Unfortunately, we know students can appear behaviorally engaged but still not get much out of school.

Cognitive engagement – the deeper psychological commitment students make in learning. In the classroom it looks like planning and persistence, goal-setting, and problem-solving.

Emotional engagement – the personal or affective investment students make in school. When students feel a sense of belonging and connection they are more likely to pose questions, seek help, and exhibit curiosity for learning.

More recently, Amy Berry created a more descriptive model of engagement that goes beyond stating that students are “participating” or not. The goal is to move students from Disrupting to Driving their own learning:

- Disrupting (others or the learning)

- Avoiding (off-task behavior)

- Withdrawing (physically or emotionally)

- Participating (doing work and paying attention)

- Investing (posing questions, appreciating learning)

- Driving (setting goals, seeking feedback, self-assessment)

Student Engagement: It’s Not About the Tools!

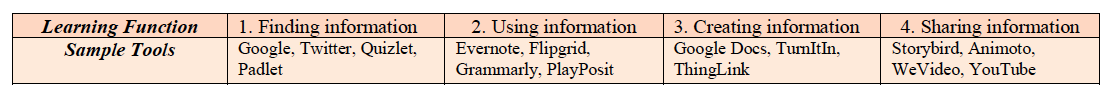

In the rush to create virtual classrooms, we focused on the tools rather than the learning and engagement. The authors advise that we now ask ourselves: What do students need to be able to do (online or in school) to be successful learners? Learners need to perform four main functions: 1) find and evaluate information efficiently, 2) use information accurately and ethically, 3) create information to inform their learning, and 4) share information responsibly with others. Students can perform these functions via traditional paper and pencil or through a shared online tool. Put another way, when it comes to engaging students in learning, the medium doesn’t matter.

The chart below shows how teachers might utilize specific tech tools to support student learning and engagement, but the tools are not the focus. Teachers who are overwhelmed by “too much technology” should review how their current choices align with these four primary learning functions and then refine their selections. Tech tool choices should be limited and consistent. Alone, with teams, or with the whole staff, choose a few tech tools and use them consistently. Additional resources are on the Corwin resource website.

Learning remotely should not be reduced to worksheet completion or busy work. Teachers must strive to engage students – to move them from merely “doing” to driving, as Amy Berry’s research (above) would support. The following tasks encourage deeper learning and engagement, whether performed independently or collaboratively.

Design Tasks with Engagement in Mind

- Open Tasks: Encourage students to think in more than one way or consider multiple perspectives by asking questions that have more than one “right answer” or posing problems that can be solved in multiple ways.

- Understanding Tasks: Help students develop deeper understanding of individual topics by asking them to make connections between them. For example, ask students to compare and contrast, identify patterns, or find connections between dissimilar ideas.

- Problem-Solving Tasks: Create tasks that challenge students to try their ideas out on their own, rather telling them what to do first. Foster a group’s reliance on one another by giving them only some of the steps or including irrelevant information so they move away from procedural knowledge toward more problem-solving skills.

Schedules to Promote Engagement

Distance learning schedules must provide consistency and predictability for students and families. Schools must ensure that there are adequate breaks between sessions, and sessions should never overlap. Additional recommendations include:

- Live sessions should be prioritized for class connections and interactions. This means some learning (e.g. direct teaching) should occur asynchronously, rather than in real time.

- Design weekly schedules with clear expectations of the tasks to complete before and after live sessions. Also include learning intentions, success criteria, and assessment information. Tip: A Distance Learner Weekly Planner (6.6) is on the resources page.

- Finally, schools must plan for potential scheduling issues. Questions to consider include: What do families need to support students (but not be burdened)? How can students independently access tech help? How can we collect questions and concerns?

Module 7 – Quality Instruction for Distance Learning

In distance learning, like traditional classrooms, teachers must be willing to change their instructional strategies to positively impact learning and engagement. The authors’ assertion is: Teachers should not hold an instructional strategy in higher esteem than their students’ learning. The goal in Chapter 7 is to provide a framework for engaging instruction that can be adapted as needed.

An Instructional Framework for Distance Learning

As educators consider the best strategies for distance learning, they should think about their existing definitions of quality instruction. The authors share their own four elements of quality instruction:

- Demonstrating: How do I present content effectively to students?

- Collaborating: How do I encourage collaboration in the learning process?

- Coaching and Facilitating: In what ways do I help guide my students’ thinking?

- Practicing: How do I ensure students practice and apply their learning?

The center of the authors’ ideal framework for instructional design represented is purpose. As discussed in Chapter 6, learning goals should drive instruction. Student activities and assignments must be aligned with these goals. The other parts of the pinwheel spin around the purpose at the center. Distance learning teachers should consider all the ways students can access their class as they design opportunities for demonstrating, collaborating, coaching and facilitating, and practice.

The Elements of Quality Instruction

Demonstrating

Demonstrations provide students with examples of what they will do or learn. Teachers can demonstrate for students through direct instruction, think-alouds, worked examples, and share sessions (to name a few). Each approach allows the teacher or student to share his or her thinking. This is important because just “showing” a student how to do something does not ensure their success. Consider it this way: How many times have you seen someone cut hair or change a tire and still feel clueless about the process? The aim of demonstrating is to make thinking visible to students. Tip: See the Chapter 7 videos on the Corwin resources website.

Collaborating

Collaboration and dialogue between students are powerful contributors to student learning (in fact, the effect size for class discussion is 0.82). Unfortunately, teachers often do most of the talking – even more so in distance learning. Teachers should not attempt to “fill time” during live sessions or rely too heavily on pre-recorded videos. Instead, they should make student collaboration an integral part of distance learning. The mindset should be: “I engage as much in dialogue as monologue.” Book clubs, jigsaw activities, discussion forums, and reciprocal teaching activities (where students teach one another) can all increase collaboration in distance learning.

Coaching and Facilitating

One of the primary ways teachers can support students in distance learning is through coaching and facilitating. These strategies focus on guiding students’ thinking while avoiding the temptation to tell students what to think. Take a closer look at each strategy below.

Questioning: Most teacher questioning follows the IRE cycle: initiate a question, get a response, and evaluate the response. This structure often utilizes questions with only one right answer. Teachers can improve their questioning by asking open-ended questions that elicit students’ opinions, ideas, and feelings. Teachers can also have students write and share their answers on response cards, rather than calling on individual students. When all students respond simultaneously, participation and test scores increase.

Prompts and Cues: Prompts assist students in completing tasks by encouraging their cognitive and metacognitive thinking. Statements such as “What do you already know about this topic?” or “What is the next logical step?” help students tap into prior knowledge and problem-solving strategies. Verbal, visual, or gestural cues shift learners’ attention to help them overcome difficulties. Examples include pointing to a key paragraph in a text that the student overlooked or using graphic organizers to arrange content.

Coaching: Targeted coaching sessions support students’ academic and emotional growth. For example, in Ms. Sandoval’s English class, she uses the information she collects while she grades student essays to provide online coaching to small groups. If she sees student groups struggling to collaborate, she works with individual groups on specific communication skills to improve.

Practicing:

Students must be given opportunities to practice their skills in order to apply them. Students’ practice must be deliberate, that is, practice with the goal of improving their performance. Teachers can support deliberate practice by reminding students of the learning goal and providing feedback on the practice. Ideally, teachers should spread out practice over time and include material from the past.

Module 8 – Feedback, Assessment, and Grading

In Module 8, the authors explore the challenge and opportunities for feedback, assessment, and grading in distance learning. Feedback and assessment are essential to teaching and learning. Formative assessments document student progress and provide relevant feedback to students. Feedback and assessment are also used to modify instruction based on learners’ needs. Summative assessments measure students’ cumulative learning, and final grades give further feedback about student mastery.

Given how important this “feedback loop” is to student success, it is no surprise that the shift to distance learning has raised concerns about how this process is impacted in virtual environments. In this section, we will explore strategies to ensure these important elements of teaching and learning are not lost in the digital space.

Effective Feedback for Students

The most important element of the feedback loop is, of course, the feedback itself: Assessments (and grades) are not particularly useful if students cannot use the information they provide to improve learning. The authors remind us that the best feedback we can provide is descriptive, supportive, and reciprocal. Let’s take a closer look at these key feedback elements below.

Descriptive: The goal with descriptive feedback is twofold: 1) help students recognize how their actions or decisions impact their performance, and then 2) help them define goals for improvement. For example, “You provided a description of the samurai caste’s rise in the introduction which provides context for your reader. You left out the key events that led to that rise. Can you find sources for this information and make a plan to include it in your next draft?” Descriptive feedback like this helps students learn by setting forth a clear picture of what success looks like.

Supportive: Students are more likely to utilize feedback when it is provided in a supportive environment. In a study of middle and high school students, 20% of students said they disregarded a teacher’s feedback because they had a poor relationship with him or her. We can increase feedback effectiveness by fostering relationships and embracing errors as part of learning. One way to do this is to use more verbal feedback in distance learning since it comes closer to matching the warmth and familiarity of in-class feedback.

Reciprocal: Teachers should also solicit feedback from their students to find out how they are experiencing their online/remote learning. This includes asking students to comment on the quality and usefulness of online materials and discuss their own participation (e.g. Have they asked questions this week? Are they keeping up with assignments?). Feedback from students can be coupled with LMS user analytics regarding student usage to ensure materials support learning.

Effective Formative Assessment

Formative assessment requires teachers to “check for understanding” throughout a lesson or unit, not just at the end. As we’ve already mentioned, the power of formative assessment is in the feedback it can provide: Successful feedback allows teachers and students to take positive actions to improve teaching and learning. Here are just a few ways to check for understanding in distance learning:

- Virtual exit slips: At the end of a lesson, students choose one of four exit slips: 1) I’m just learning this, 2) I’m almost there, 3) I own it! or 4) I can teach others. Teachers use this information to plan targeted support, such as live tutoring or recorded tutorials.

- Virtual retellings: Elementary teachers record their reading of a book and ask students to listen to the story and practice retelling it at home. Different students submit their retellings for feedback each week – this provides feedback to the teacher and student.

- Student polls: With the use of apps like Kahoot! teachers can solicit student responses to multiple-choice questions and quickly assess understanding or gather data regarding student opinions.

- Ungraded practice tests: When ungraded, short quizzes support learning by giving students the change to reflect on their learning.

Effective Summative Assessment

Summative assessments are used to determine students’ learning at the end of a unit or course. To be effective, the assessment content must reflect the unit’s standards, but the design can vary. Below are some considerations for assessment design in distance learning.

- Expand testing formats: Teachers may have concerns about how to proctor traditional exams online, but there are many forms of assessment. For example, while oral tests are almost impossible in class due to time constraints, students in online classes can record their responses for the teacher to view individually. If teachers need to use traditional exams, they can keep the test short and use timed live sessions to proctor them – students just need to have their cameras on so they can be observed.

- Emphasize academic honesty: Be proactive by discussing honesty and ethical decision-making frequently in class. Teachers should also provide a statement of academic honesty in the first weeks of school (and post it in the LMS). Some schools also include a statement of academic honesty in summative assessments for students to sign.

- Use text-matching software for essays: Plagiarism detection programs are valuable in any environment. The key is to teach students about these programs rather than just using them to “catch” students at the end.

The Advantage of Competency-Based Grading

Most teachers will tell you that grades reflect students’ mastery of a content or skill, but upon closer inspection, grades often reflect nonacademic behaviors as well. When teachers weave behaviors such as timeliness, perceived effort, or participation into a grade meant to reflect student mastery, it compromises the accuracy of the report. This is not to say that these behaviors are not important, but they should not be included in grades or interfere with the focus on mastery.

Schools should consider competency-based grading to maintain accuracy. In these systems, students’ grades are based solely on their ability to demonstrate mastery of the standards (not practice work like homework). Typically, this means students must pass summative assessments in order to pass a class. Students who do not earn passing scores are provided additional practice, tutoring and test retakes. While competency-based grading is not easy to implement, and not all schools can consider it now, it is beneficial in distance learning because it centers on skill-building and removes the “complexity” of how to grade online homework or participation.

Module 9 – Using What We’ve Learned from Crisis Teaching

As Winston Churchill supposedly said, “Never let a crisis go to waste.” While the scale of the current global crisis was unprecedented, our schools’ abilities to respond rapidly was not (ask any educator who taught in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina or the bush fires of Australia).

Not surprisingly, after these recent crises, the focus for schools was on a “return to normalcy.” There was little desire to identify lessons learned and act upon them. The authors implore schools not to make this mistake again: Schools must learn from our current situation about what to do better now and in the future.

Learning from Other Crises

As we look for ways to make learning better, there are several takeaways to consider from previous school crises, such as:

- After Hurricane Katrina, teachers and students who had a prior history of mental health issues were more likely to show symptoms. This emphasizes the importance of social and emotional support for impacted school communities.

- Studies completed after Australia’s Christchurch earthquakes showed that community members felt closer because of their shared experience. Schools can benefit by embracing and building on this sense of shared community with students and parents.

- Despite the Katrina and Christchurch crises, students were able to bounce back academically. This was due in part to the fact that teachers tailored learning specifically to what students could NOT do – essentially, they were “triaging” learning for students rather than teaching (or reteaching) tasks that students could already do. Both situations show that with the right supports, student academics do not need to suffer long-term effects.

Using Crisis Learning to Make Schools Better

Schools have already learned important lessons from the current pandemic, including the value of partnering with parents, and the vital connection between the social and emotional elements of learning and the academic ones. Schools have also learned that ineffective classroom practices are ineffective in digital spaces, too. Too much lecture and too many worksheets are not effective in any environment. So, what can we do to make future learning better for students and teachers? The authors suggest the following:

Make Learning Better for Students:

- Collect early feedback on what students know and don’t know. Focus your valuable teaching time on the things they don’t know (instead of reviewing things they do). This was one of the most important lessons from the Christchurch earthquakes.

- Build in mechanisms to provide timely feedback for students. Feedback is necessary to inform instruction and support growth!

- Create opportunities for social interaction. Use technology and social media for students to share, interact, and work together.

- Focus on subjects that parents are least likely to be able to help with (e.g. math or science).

- One big benefit to online learning is students have the ability to watch recorded lessons multiple times in order to improve their knowledge and skills. Design practice and assessment strategies to allow students to take advantage of this opportunity.

- Do not depend on parents to help students get “unstuck” if they have a question, make an error, or do not know what to do next.

Make Learning Better for Teachers:

- Help teachers grow professionally by exploring different ways to assess the impact of their teaching in distance learning.

- Build school teams where teachers can work collaboratively to share their practices and promote social togetherness.

- Support empathy and understanding between parents and teachers, especially regarding the challenges both groups face.

- Encourage the mindset that current distance learning challenges can be growth opportunities: Teachers can use their experiences to design better supports for students.

One of the greatest messages in this chapter (and perhaps from the entire book) is that schools can and should leverage their strengths, including what they have learned from crisis online teaching, to prepare for more robust and authentic learning in the future.

© The Main Idea